THE WINDOW - DAS FENSTER

Kate Baker » Sibylle Bergemann » Lillian Birnbaum » Elmer de Haas » Heinz Hajek-Halke » Monique Jacot » Hannes Kilian » Birgit Kleber » Barbara Klemm » Jens Knigge » Robert Lebeck » Herbert List » Stefan Moses » Rita Ostrovska » Ulrike Ottinger » Marek Poźniak » Beat Presser » Sheila Rock » Michael Ruetz » Max Scheler » Liselotte Strelow » Karin Székessy » Donata Wenders » Kurt Wyss »

Exhibition: 21 Mar – 13 Jun 2015

Johanna Breede PHOTOKUNST

Fasanenstr. 69

10719 Berlin

+49 (0)30-88913590

photokunst@breede.de

www.johanna-breede.com

Tue-Fri 11-17, Sat 11-14

"THE WINDOW"

Exhibition: 21 March – 13 June, 2015

We alone are the insiders of our interior worlds. Within ourselves we feel safe and yet often isolated and sealed off. At the same time, hope is almost always contained therein: evident itself in windows, in the gates of the eyes. Each window is a link, a step between the interior and the exterior. The window functions just as with the lens of a camera - it is the point between the camera obscura and the outside. The point where light breaks through and illuminates another world.

Alfred Hitchcock recognized this relationship quite early on. In his 1954 masterpiece "Rear Window" he plays with the analogies between the window and photography. A superficial crime story in a small room, the film is actually about a physically impaired photographer who, in turn, acts as a metaphor for the possibilities and limitations of the instruments of sight.

Photographers, for Hitchcock, are handicapped. Inside the four sides of their pictures, they condense characters and narratives; they provide clues. They capture restricted views. But the full picture is composed inside the mind. The world within a picture - as in the frame of a window - always contains only half of the truth.

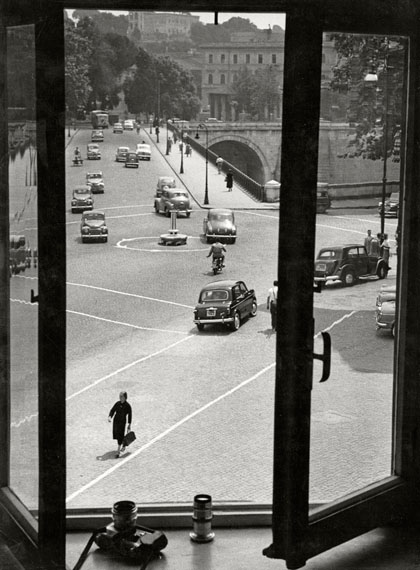

Photography’s history is full of the gaze from the window, in the window and through the window. We see this already in one of the world’s first photographs - Joseph Nicéphore Niépce’s image peering out the window of his work room in Le Gras (1826). Further famous window vistas come from photographers ranging from Louis Daguerre to Andreas Gursky.

Photographers may be lured to such scenes due to the often unusual light, but perhaps more so because they are drawn into the view of the open. Many more images of windows contain the history of the photographic gaze itself - a history of the voyeur’s secret peephole; of this protected seat from which to view the theatre of the world.

Johanna Breede PHOTOKUNST Gallery, dedicates their upcoming exhibition to all these architectural interfaces. More than 60 pictures from 24 photographers testify to the wide range of challenges that windows have presented to artists. Their possibilities range from a wide view on the world to the reflection of the inner self. For this group exhibition, we have sifted through the archive of photo artists such as Stefan Moses, Robert Lebeck, Barbara Klemm, Sybille Bergemann or Donata Wenders, and have chosen their most beautiful window views. There is, for instance, Kurt Wyss’ view out the hotel window in New York City.Between the interior and exterior is a TV set. On the TV screen we see the former US President John F. Kennedy presenting a speech. Wyss, born in 1936, skillfully mixes not only natural and technical vistas, but he calls attention to the fact that monitors also act as windows - openings to the world, whose transparency is always a one way street.

Max Scheler, on the other hand, knows that windows don’t only open, but they can separate. One of the images in the exhibition from this renown Stern photographer shows the former Beatle, George Harrison, standing before the closed windows of a train car. From the other side of the glass his fans stare on, like fish in an aquarium. It is by no means evident who is on the inside and who is on the outside - who is free and who is the prisoner.

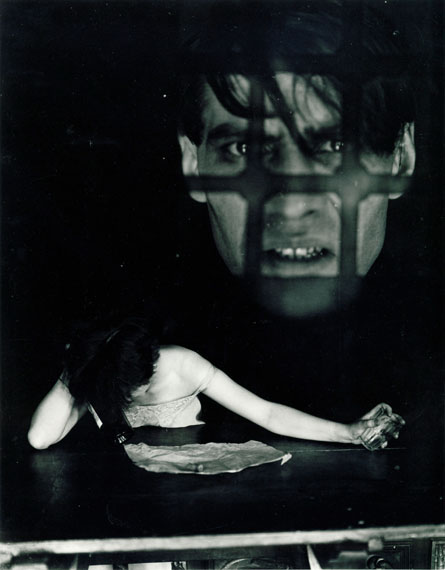

And finally, an image from the photographer Heinz Hajek-Halke, who died in 1983. His photomontage "Sexual Deprivation of Prisoners" from 1926 is not only the oldest, but also the most experimental work in the exhibition. Hajek-Halke illustrates the barred face of a inmate, staring out at a gigantic figure in the foreground. It is a mixture of forensic illusion and photographic caution: imprisoned in the inner soul, man can quickly be overpowered by wandering delusion. Windows can be salvation; they can be breakthroughs in the thickest of darkness. (Text: Ralf Hanselle, translation: Sondra Kitchen)

�

"DAS FENSTER"

Ausstellung: 21. März bis 13. Juni 2015

Wir sind die Insider unserer je eigenen Welten. Im Interieur unserer selbst fühlen wir uns sicher, zuweilen aber auch isoliert und abgeschottet. Dabei enthält fast jeder Innenraum auch eine Hoffnung: Sie manifestiert sich in Fenstern, Durchgucken, Augentoren (ahdt.: augadoro). Denn jedes Fenster ist eine Verbindung; eine Schnittstelle zwischen innen und außen. Es funktioniert so gesehen wie die Linse eines Fotoapparates – es ist ein Spalt zwischen "Dunkler Kammer" (camera obscura) und Außenraum. Ein Lichtdurchbruch. Ein Weltenspender.

Schon Alfred Hitchcock hatte diese Verwandtschaft früh erkannt. In seinem 1954 gedrehten Meisterwerk „Das Fenster zum Hof“ erzählt er von den Analogien zwischen Fenster und Photographie. Vordergründig eine Kriminalgeschichte auf kleinem Raum, ist der Film um einen gesundheitlich lädierten Photographen auf den zweiten Blick eine Metapher über die Möglichkeiten und Handicaps des apparativen Sehens. Photographen sind für Hitchcock Eingeschränkte. Innerhalb der vier Seiten ihrer Bilder verdichten sie Zeichen und Narrationen. Sie schaffen Andeutungen. Sie fixieren eingeengte Außenblicke. Das ganze Bild aber entsteht erst im Kopf. Die Welt zwischen Bild- wie Fensterrahmen ist immer nur die halbe Wahrheit.

Blicke auf Fenster, in Fenster und durch Fenster hindurch: die Geschichte der Photographie ist voll von ihnen. So zeigt bereits das weltweit erste Photo – Joseph Nicéphore Niépces Blick aus seinem Arbeitszimmer in Le Gras (1826) – eine Aufnahme aus einem Fenster. Weitere berühmte Fenster-Durchblicke reichen von Louis Daguerres bis zu Andreas Gursky. Dabei ist es vermutlich nicht nur die immer wieder ungewöhnliche Lichtsituation, die Photographen an den Blicken ins Freie gereizt haben. Vielmehr erzählen Fenster Geschichten über das photographische Sehen selbst – über das geheime Guckloch eines Voyeurs; über den geschützten Blick auf ein Welttheater.

Die Galerie Johanna Breede PHOTOKUNST widmet sich in ihrer kommenden Ausstellung ganz diesen architektonischen Schnittstellen. Über 60 Aufnahmen von 24 Photographen werden von den unterschiedlichsten Herausforderungen zeugen, die Fenster für Photographen gespielt haben. Ihre Möglichkeiten reichen vom geweiteten Weltblick bis zur Rückspiegelung des eigenen Selbst. Die Archive von Photokünstlern wie Stefan Moses, Robert Lebeck, Barbara Klemm, Sybille Bergemann oder Donata Wenders werden für diese Gruppenausstellung daher nach ihren schönsten Fensterblicken befragt. Da ist etwa Kurt Wyss' Aussicht aus einem Hotelfenster in New York City. Zwischen Innenraum und Außenraum ist ein Fernseher positioniert. Auf diesem läuft eine Ansprache des einstigen US-Präsidenten John F. Kennedy. Geschickt vermischt der 1936 geborene Wyss nicht nur natürliche und technische Fernblicke; er macht darauf aufmerksam, dass auch Monitore Fenster sind – Weltöffnungen, deren Transparenz immer nur zu einer Seite hin gegeben ist.

Max Scheler wiederum verweist darauf, dass Fenster nicht nur Öffnungen, sondern auch Trennungen sein können. Ein Ausstellungsbild des einstigen Stern-Photographen zeigt den damaligen Beatle George Harrison vor dem verschlossenen Fenster eines Zugabteils. Auf der anderen Seite des Glases starren Fans wie Fische aus einem Aquarium heraus. Doch längst ist nicht ausgemacht, wer hier drinnen und wer draußen ist – wer Freigänger und wer Gefangener.

Und mit Einschließung spielt auch eine Aufnahme des 1983 verstorbenen Heinz Hajek-Halke. Seine Fotomontage "Sexual Deprivation of Prisoners" aus dem Jahr 1926 ist vermutlich nicht nur die älteste, sondern auch die experimentellste Arbeit der Ausstellung. Hajek-Halke zeigt das vergitterte Gesicht eines Gefangenen, das übergroß auf eine angedeutete Figur im Vordergrund starrt. Es ist eine Mischung aus forensischem Wahn und photographischer Warnung: Eingekerkert im Interieur einer Seele, wird man schnell überwältigt von Trugbildern und Irrlichtern. Fenster sind somit immer auch Rettung. Sie sind Durchbrüche aus Dunkelheiten. (Text: Ralf Hanselle)�